|

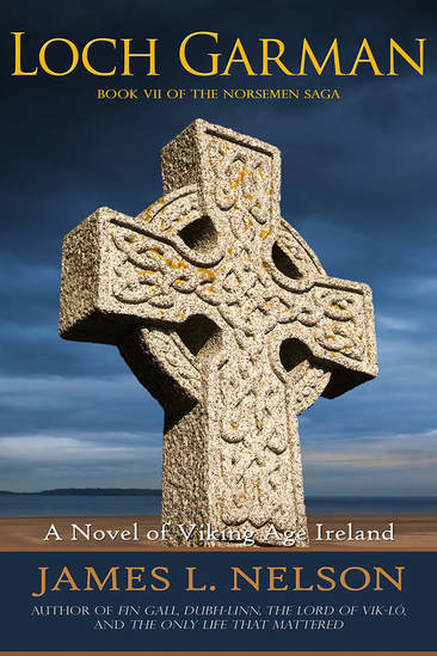

Driven ashore on the coast of Ireland, their longships nearly wrecked by the gods who seem unwilling to let them leave, Thorgrim Night Wolf and his band of Northmen once again face a fight for their survival. Helpless without their ships, they must find some refuge in that hostile country and begin the laborious work of making the vessels seaworthy again. But for all the shipbuilding skills that Thorgrim and the others possess, there is one thing they cannot do—weave cloth to replace the sails shredded in the gale that drove them ashore. For that they must strike a bargain with the Irish, the very people who most want them dead. But no such bargain can last for long, and soon betrayal and deceit have the Northmen trapped by an enemy determined to crush them once and for all.

|

Loch Garman sample chapter

|

Why do you not lament him, friends?

His death is good cause for a general mortality, It is as a cloud reaching to the saints of heaven. – Annals of Ulster |

There were two walls encircling the monastery at Ferns. The inner one was made of stone. It was called a vallum and it was not intended as any sort of defense, at least not from an earthly threat. It was no more than three feet high and it enclosed the sacred monastic buildings—the church and the scriptorium—and those somewhat less sacred but important nonetheless—the monks’ cells and the abbot’s house and the larger building where the cloistered nuns lived and worked. The vallum marked the edge of sanctuary.

The second wall stood several hundred yards away from the vallum and it was a more substantial affair: an earthen rampart built up to a height of ten feet with a palisade fence mounted on top. Between the vallum and the outer wall were located the fields that grew a good portion of the food that fed the monastery, the round thatch and wattle homes of the lay people who carried on the work that the priests, monks or nuns did not. There was a brewer and a blacksmith and several woodworkers. There were stables and a creamery.

Ferns, like so many of the monasteries of Ireland, had grown to something beyond its origins as a holy site, like some oak tree that, as it grows, finds itself host to birds and squirrels and sundry insects and rabbits and badgers making their homes around its roots. And, like the oak, once it had grown sufficiently big and valuable, inevitably someone would arrive carrying an ax.

The heathen Northmen had come several times. They had looted and burned and enslaved. But that had not happened for some while, and Abbot Columb, who had been overseeing the monastery for many years, and had lived there for many, many years before that, had allowed himself to hope that God had taken that cup from his hands.

And perhaps He had. But Northmen were not the only threat. And now the men with the axes were back. Axes and swords, shields and spears.

Abbot Columb sighed.

Mounted as he was on horseback—a rarity for him and thankfully so—his eyes were near level with the top of the heavy oak-plank gate that closed over the eastern entrance through the outer wall. He looked at the dense wood, dark brown with the soaking rain, through a steady drip of water off the edge of the cowl he had pulled up over his head.

“Dear Lord,” he said, “if you could see fit to allow me to catch my death in this rain, I would look upon it as a great blessing.” But he did not think the Lord would oblige that easily. He had lived through six decades and a smattering of years, through sundry diseases and injuries, though several sackings by the Northmen. He did not think that the rain, cold and driving as it was, would be the end of him.

He nodded to the frightened-looking men standing ready to swing the big doors open. They nodded back, and one at least made the sign of the cross; then they leaned back into the weight and the gate swung open.

The muddy ground on which the abbot’s horse stood seemed to spill out of the gate and form itself into something like a road, the main avenue from Ferns to the sea to the east and, through various by-ways, to Glendalough to the north and Dumamase to the northwest and beyond that Abbot Columb did not care.

On the clearest of days the abbot, standing where he now stood, could see for miles over the rolling green hills of Laigin. But on that particular morning the sky had closed in and the hills were lost in fog and a hundred armed men stood in a line across the road. Abbot Columb sighed again and kicked his horse in the flanks, prodding the beast to a walk. Behind him he heard the gates swing closed again.

For fighting men they were not all that impressive, Columb noted. Those near the center of the line, and on the flanks, were full-fledged men-at-arms, the house guard, no doubt. Trained and loyal. But those in the center of the ranks did not look so enthusiastic. They leaned on spears and held shields loose at their sides or, in more than a few instances, over their heads to ward off the rain. Men who were concerned about getting wet were not men primed and ready for battle.

A dozen feet ahead of the line a man sat astride his horse, waiting. The horse, a big stallion, black with a thick mane, was far more impressive than the tired nag on which the abbot rode. The man on the stallion, wearing mail and a steel helmet, flanked by four of his house guard, was far more impressive than the abbot himself. Airtre mac Domhnall, the rí tuath of the lands east of Ferns. A genuine horse’s ass, in the abbot’s opinion.

Abbot Columb brought his horse to a stop fifteen feet from where Airtre mac Domhnall and his men sat waiting. “So, Airtre, what brings you to my doorstep?” he called. His voice was not as strong as it once was, and that annoyed him.

“You know why I’m here, Abbot,” Airtre said.

Columb shook his head. He did in fact know why Airtre was there, with armed men, but he wanted to make Airtre say it.

“I can’t imagine what would bring you out on such a day,” the abbot said.

“You are the keeper of the Treasure of St. Aiden,” Airtre said, holding up his hand to stop Abbot Columb’s denial before it began. “Don’t bother denying it; you waste your breath. I know the treasure exists. I’ve been told by men I trust. A portion of it is owed to me, as rí tuath. I have come to collect it.”

Abbot Columb sighed.

“You are not rí tuath over these lands, and even if you were it would give you no authority over the Church,” the abbot pointed out. Airtre mac Domhnall, of course, was well aware of all that. He was not collecting taxes due him; he was raiding the monastery, but also looking for some veneer of an excuse for doing so.

“That is a matter of some dispute,” Airtre said. He wiped the rain from his face and ran gloved fingers through his beard.

“Tuathal mac Máele-Brigte is rí ruirech, the high king,” Columb replied. “If you feel you should enjoy a share of a treasure that does not exist, you must take the matter up with him.”

Airtre smiled. “Tuathal is quite a distance from here, and he has his hands full trying to keep his own family from cutting his throat. And I don’t think he will succeed.”

This was true, and Columb knew it. There was great intrigue and a struggle for power among those who aspired to rule Laigin, as there so often was, and Airtre was happy to capitalize on the confusion.

“See here,” Airtre continued, and Columb could hear the man’s patience draining away. “I am done discussing the matter. Pray, open the gates and let my men through. I don’t wish any harm to the monastery. I want only to take what is rightfully mine.”

“You are truly a man of God,” Columb said, his voice flat, with no hint of either sincerity or irony. “There is nothing I can do. Even if I keep the gates shut, our sorry dirt walls will not hold you out for long. So give me leave to warn the sisters of your coming that they might retreat to their house, and then we will open the gates.”

“Very well, Abbot,” Airtre said, with traces of both triumph and suspicion in his voice. “My man Ailill will accompany you, if that’s acceptable.”

Abbot Columb shrugged. It did not matter to him. So the man at Airtre’s left side spurred his horse forward, and as he approached Columb, the old abbot turned his own mount, and side by side they rode toward the monastery’s gate, which was swinging open to greet them.

The Treasure of St. Aiden… Columb mused as he rode through the driving rain. Here was an ancient tale that had plagued him for years, and abbots of the monastery before him. No one, of course, believed that the treasure had been secured by St. Aiden himself, who had founded the monastery almost three hundred years earlier. That was simply the name given to this alleged hoard of gold and silver and such that was supposedly hidden somewhere within the walls, hidden so well it had been overlooked by the successive bands of Northmen who had sacked the place.

Neither Columb nor anyone else knew where this legend had come from. It was true that Ferns was a wealthy monastery, and the abbot and a few others, a very few, knew the truth of why that was. But there was certainly no Treasure of St. Aiden.

At least he has not gone up into the hills, Columb thought. If there was one advantage to the legend of the treasure, it was that men like Airtre or the heathens before him came looking for riches at the monastery and did not go blundering around the hills to the north. And that, to the abbot, made this sort of annoyance, the sort that Airtre was visiting on them, worth it.

The abbot glanced over at the man named Ailill who was riding beside him. They walked their mounts through the gates. Columb pulled his reins a bit and his horse veered off to the right and Ailill did likewise.

There was a cocky arrogance on the man’s face, so typical of these young warriors, Columb thought. They rounded the end of the gate where dozens of armed and mounted men in the abbot’s service had been hidden from view. Columb tried not to take any satisfaction as he saw Ailill’s expression turn from haughty to surprised to panicked.

Ailill began to make a strangled cry, but before he could get much sound clear of his throat, four men were on him, dragging him down from his saddle and into the mud. Three of the men pressed feet down on his shoulders and legs while the fourth used his foot to press the man’s face down in the soft earth to keep him from crying out.

Standing over the man, sword drawn, was Brother Bécc mac Carthach. Brother Bécc was wearing a padded tunic under a mail shirt, and there was nothing in his dress or gear that would suggest he was a monk—which he was—save for the large, crude wooden cross that hung from a leather thong around his neck.

Bécc looked up at Columb, his long dark hair plastered to his head. Only one eye, the left eye, was visible on his half-ruined face. The other eye, along with the flesh on the right side of his face, right down to the bone, had been eliminated by the downward slash of a Northman’s sword in a fight long before Bécc had sought refuge in the church.

Incredibly, the man had not died. Hard scar tissue had grown over the place where his eye and his skin had once been, and Bécc had given thanks to God and devoted his life to the service of his Lord, bringing his devotion and his particular abilities to that cause.

Now, as ever, he looked to Columb for direction. Columb shook his head. No more communication was needed, and Ailill did not even know that the abbot had just spared his life. Bécc gestured toward one of his men, who stepped over and quickly gagged and bound Airtre’s squirming man-at-arms.

Columb turned his eyes from Ailill, still sprawled in the mud, to another man, mounted, wearing mail and a helmet, sword also drawn, watching from a dozen feet away. The man looked up from the thrashing Ailill and met Abbot Columb’s eyes. The abbot nodded his head to this one as well, and as with Bécc, no more words were needed.

The mounted man, named Faílbe mac Dúnlaing, raised his sword and shouted, “Go! Go!” He kicked his heels into his horse’s flanks and the beast leapt forward and the men behind did likewise, twenty horses streaming past Abbot Columb and his tired mare, and behind them another forty men on foot, armed with spears and axes and many wearing leather armor and bearing shields. Faílbe was the rí tuath of the lands to the west of Ferns, a friend of the monastery, a wealthier man than Airtre, and soon wealthier still once Columb compensated him for his efforts in driving Airtre away.

As those men who had gathered for the defense of Ferns charged out of the gate, Brother Bécc mounted and led the monastery’s twenty-man house guard after them, so that they, too, might join in the fight. Columb might not have the Treasure of St. Aiden, but he was not without resources.

As the last of the soldiers raced past, Columb swiveled his horse around and took a few steps forward to where he could see out the still-open gates to the battlefield, if such it could be called, beyond.

The mounted warriors streaming out of the monastery gates seemed to have taken Airtre and his men entirely by surprise. The Irish did not as a rule fight mounted. They were more likely to use their horses to get to a fight and then dismount and do battle on foot. But Columb and Faílbe had agreed that the terrifying sight of a massive horse and sword-wielding rider pounding down on them might be just the thing to make Airtre’s men break and run.

And they were right. Columb could not see much, with the rain and the distance and the press of men, but he could see the soldiers who formed Airtre’s line frantically taking up their shields and positioning their weapons and bracing for the shock of the riders barreling into them.

Airtre himself and his men-at-arms were not so thrown off by the surprise. They began to move immediately, riding toward the threat, swords held high, spears leveled. But Faílbe’s men all but ignored them, going instead for the vulnerable, lightly armed, frightened men in the line.

It worked just as they had hoped. The horsemen were still fifty feet away when the first of Airtre’s unhappy, conscripted soldiers flung his weapons aside and ran, followed almost instantly by the next and the next. By the time the riders reached the place where the men had been making their stand, they were all in flight.

Despite that ignominious retreat, there were still some men ready to fight. Airtre and his warriors, too proud to run without first making a stand, spurred their horses forward to meet the attack. They charged into Faílbe’s riders, exchanging blows with swords, lunging with spears, swirling around and around in that odd dance of mounted combat. The ring of steel on steel, the shouts of fighting men came in sharp bursts through the muting rain.

Columb watched with interest. The only question really was how long Airtre and his men would keep it up before they, too, ran off, and if many would die before they did. Columb really did not care to see men die, not even men like Airtre, and he said a silent prayer that God might break Airtre’s will and send him running off.

It was not long at all before the prayer was answered. The fight was entirely one-sided, hopeless for Airtre and his men-at-arms once they had been abandoned by most of their men. First one of Airtre’s guard, then another and another broke off from the melee, spun his horse around and raced off down the muddy road, where the foot soldiers were already nearly lost to sight. Airtre was last to go, but go he did, and well before his escape could be cut off.

Brother Bécc was willing, indeed eager, to pursue Airtre to the end of the earth and tear the man’s liver out when he got there. But he had only twenty men under his command, and that was not enough, even against such poor soldiers as those Airtre commanded, and Faílbe’s men had no intention of pursuing the defeated men.

This, too, was planned. Much as Columb loathed Airtre and his greed and ambitions, he did not want to precipitate a slaughter of Airtre’s men. Faílbe, for his part, did not care to go chasing all over the countryside while leaving his own tuath unprotected. So it was agreed: Faílbe would drive the insolent raiders away from the monastery at Ferns, but would do no slaughter beyond that.

And Faílbe was a man of his word. His horsemen chased Airtre’s no more than a hundred yards down the road, making no real effort to catch them, then reined to a stop and watched them racing off over the dull green fields. When at last they were certain that the raiders were leaving and would not be back soon, they turned and walked their mounts back toward the monastery gates.

A few men lay on the battlefield, wounded, perhaps killed, and Abbot Columb moved his horse to one side to allow a cart to pass through the gates to collect them up. Faílbe and Brother Bécc rode past the wounded with hardly a glance. They came in through the gate, their men-at-arms, mounted and otherwise, trailing behind. They reined to a stop in front of the abbot.

“I congratulate you on the victory God has given you,” Columb said. Faílbe nodded, gave a weak smile as if he found that idea slightly amusing and nothing more. Brother Bécc crossed himself and bowed his head, then looked up again.

“There is food and ale and a fire in the hall for you and your men,” Columb said next, and that was greeted with greater enthusiasm.

True to Columb’s promise, the food and drink were plentiful, the fire in the hearth in the center of the floor built to a height that nearly threatened the thatch overhead, and it was not long before Faílbe and his men were full and nearly dry, their corporeal needs satisfied at least, and that was as much as Columb could hope to do. The abbot did not think they were the sort who worried too much about their spiritual needs.

“Let me raise a glass, Abbot,” Faílbe said.

He and the abbot were seated at the head table, the remains of their meal in front of them, the light of the fire dancing off their steaming clothing. Bécc, too, sat with food and drink in front of him, but there was nothing that Columb could read on the man’s face. That was usually the case. He wondered if that was because of the monk’s natural stoicism or the damage his face had endured. Both, the abbot concluded

Columb lifted his cup. Faílbe had already raised quite a few glassfuls to his lips, but Columb would begrudge him nothing after the aid he had given that day.

“To the Treasure of St. Aiden,” Faílbe said. His face was adorned with his half-amused smile so Columb raised his glass higher still.

“To the Treasure of St. Aiden,” Columb said. “May it continue to not exist. As a story for children it is trouble enough. I can’t think what agonies it would bring if it were real.”

The two men smiled. And drank. And Brother Bécc drank and said nothing.

The damned Treasure of St. Aiden… Abbot Columb thought.

“Well, I thank you, Faílbe mac Dúnlaing,” Columb said next, “for coming to the aid of the monastery. The Lord looks kindly on such things.”

“Let us hope,” Faílbe said. “I can use all the help I can get. But of course I am happy to come to your aid, Abbot, when I am able. Which I am now, but might not be soon.”

“Things are stirring to the north?” Abbot Columb asked.

“Things are stirring in the household of the rí ruirech, Tuathal mac Máele-Brigte,” Faílbe said. “There are those in his family who would cut his throat to gain the rule of Laigin, and I think they soon will. Right now they're all too busy intriguing against each other to worry about us here. But if Tuathal is killed, his successor might turn his attention this way. And if that happens I will be lucky to save myself, let alone a monastery.”

“We will pray that does not happen,” the abbot said.

A sudden draft made the candle flames dance, the sound of the rain came louder, and the two men looked up to see the door to the hall flung open. A very wet, very weary messenger stood in the frame, looking for the one to whom he should speak. His eyes settled on the abbot and his guest, men of obvious authority, and he pulled the door closed and hurried over.

“This does not bode well,” Faílbe said as the two watched the rider approach.

“Abbot Columb?” the man asked, stopping at the head table and giving a shallow bow.

“Yes,” Columb said. “And this is Faílbe mac Dúnlaing, to whom you should also give honor.”

The rider looked at Faílbe, gave another shallow and impatient bow, then turned back to Columb. “I come from Abbot Donngal, from the monastery at Beggerin,” the man said.

Columb nodded. The monastery was about fifteen miles south, overland, right at the mouth of the River Slaney. “Yes?” he said.

“The abbot begs to say that the Northmen have landed there!” the messenger gasped. He had clearly been wanting to get these words out for some time.

“The heathens! There are hundreds of them, many hundreds, and a fleet of ships, and he is sure they are set on slaughter!”

Columb nodded again, unable to work up as much enthusiasm as the wet rider. “I see,” the abbot said. “And is there anything Donngal would have me do about this?”

The messenger straightened a bit, frowned a bit. “Well, if there are any who could come to the aid of Beggerin, the abbot says that would be most pleasing to God.”

God, indeed, Abbot Columb thought. “Well, there is naught that Ferns can do. We have only a small house guard, not much more than does Beggerin.” He turned to Faílbe. “What say you? Can you bring your men to aid Beggerin?”

“I cannot,” Faílbe said. “Once the heathens have had their way with Beggerin they will come up the rivers, and that means they will soon come to my lands. It’s my duty to see to the safety of my own people first.”

Columb turned back to the young man standing wide-eyed before him. “Please tell your abbot what you heard here, and thank him for his warning. I am sure God will protect Beggerin from the ravages of the heathen. But first I beg you to dry yourself and have some food and drink. On a night such as this, I don’t think that the heathens will be at our doors anytime soon.

The second wall stood several hundred yards away from the vallum and it was a more substantial affair: an earthen rampart built up to a height of ten feet with a palisade fence mounted on top. Between the vallum and the outer wall were located the fields that grew a good portion of the food that fed the monastery, the round thatch and wattle homes of the lay people who carried on the work that the priests, monks or nuns did not. There was a brewer and a blacksmith and several woodworkers. There were stables and a creamery.

Ferns, like so many of the monasteries of Ireland, had grown to something beyond its origins as a holy site, like some oak tree that, as it grows, finds itself host to birds and squirrels and sundry insects and rabbits and badgers making their homes around its roots. And, like the oak, once it had grown sufficiently big and valuable, inevitably someone would arrive carrying an ax.

The heathen Northmen had come several times. They had looted and burned and enslaved. But that had not happened for some while, and Abbot Columb, who had been overseeing the monastery for many years, and had lived there for many, many years before that, had allowed himself to hope that God had taken that cup from his hands.

And perhaps He had. But Northmen were not the only threat. And now the men with the axes were back. Axes and swords, shields and spears.

Abbot Columb sighed.

Mounted as he was on horseback—a rarity for him and thankfully so—his eyes were near level with the top of the heavy oak-plank gate that closed over the eastern entrance through the outer wall. He looked at the dense wood, dark brown with the soaking rain, through a steady drip of water off the edge of the cowl he had pulled up over his head.

“Dear Lord,” he said, “if you could see fit to allow me to catch my death in this rain, I would look upon it as a great blessing.” But he did not think the Lord would oblige that easily. He had lived through six decades and a smattering of years, through sundry diseases and injuries, though several sackings by the Northmen. He did not think that the rain, cold and driving as it was, would be the end of him.

He nodded to the frightened-looking men standing ready to swing the big doors open. They nodded back, and one at least made the sign of the cross; then they leaned back into the weight and the gate swung open.

The muddy ground on which the abbot’s horse stood seemed to spill out of the gate and form itself into something like a road, the main avenue from Ferns to the sea to the east and, through various by-ways, to Glendalough to the north and Dumamase to the northwest and beyond that Abbot Columb did not care.

On the clearest of days the abbot, standing where he now stood, could see for miles over the rolling green hills of Laigin. But on that particular morning the sky had closed in and the hills were lost in fog and a hundred armed men stood in a line across the road. Abbot Columb sighed again and kicked his horse in the flanks, prodding the beast to a walk. Behind him he heard the gates swing closed again.

For fighting men they were not all that impressive, Columb noted. Those near the center of the line, and on the flanks, were full-fledged men-at-arms, the house guard, no doubt. Trained and loyal. But those in the center of the ranks did not look so enthusiastic. They leaned on spears and held shields loose at their sides or, in more than a few instances, over their heads to ward off the rain. Men who were concerned about getting wet were not men primed and ready for battle.

A dozen feet ahead of the line a man sat astride his horse, waiting. The horse, a big stallion, black with a thick mane, was far more impressive than the tired nag on which the abbot rode. The man on the stallion, wearing mail and a steel helmet, flanked by four of his house guard, was far more impressive than the abbot himself. Airtre mac Domhnall, the rí tuath of the lands east of Ferns. A genuine horse’s ass, in the abbot’s opinion.

Abbot Columb brought his horse to a stop fifteen feet from where Airtre mac Domhnall and his men sat waiting. “So, Airtre, what brings you to my doorstep?” he called. His voice was not as strong as it once was, and that annoyed him.

“You know why I’m here, Abbot,” Airtre said.

Columb shook his head. He did in fact know why Airtre was there, with armed men, but he wanted to make Airtre say it.

“I can’t imagine what would bring you out on such a day,” the abbot said.

“You are the keeper of the Treasure of St. Aiden,” Airtre said, holding up his hand to stop Abbot Columb’s denial before it began. “Don’t bother denying it; you waste your breath. I know the treasure exists. I’ve been told by men I trust. A portion of it is owed to me, as rí tuath. I have come to collect it.”

Abbot Columb sighed.

“You are not rí tuath over these lands, and even if you were it would give you no authority over the Church,” the abbot pointed out. Airtre mac Domhnall, of course, was well aware of all that. He was not collecting taxes due him; he was raiding the monastery, but also looking for some veneer of an excuse for doing so.

“That is a matter of some dispute,” Airtre said. He wiped the rain from his face and ran gloved fingers through his beard.

“Tuathal mac Máele-Brigte is rí ruirech, the high king,” Columb replied. “If you feel you should enjoy a share of a treasure that does not exist, you must take the matter up with him.”

Airtre smiled. “Tuathal is quite a distance from here, and he has his hands full trying to keep his own family from cutting his throat. And I don’t think he will succeed.”

This was true, and Columb knew it. There was great intrigue and a struggle for power among those who aspired to rule Laigin, as there so often was, and Airtre was happy to capitalize on the confusion.

“See here,” Airtre continued, and Columb could hear the man’s patience draining away. “I am done discussing the matter. Pray, open the gates and let my men through. I don’t wish any harm to the monastery. I want only to take what is rightfully mine.”

“You are truly a man of God,” Columb said, his voice flat, with no hint of either sincerity or irony. “There is nothing I can do. Even if I keep the gates shut, our sorry dirt walls will not hold you out for long. So give me leave to warn the sisters of your coming that they might retreat to their house, and then we will open the gates.”

“Very well, Abbot,” Airtre said, with traces of both triumph and suspicion in his voice. “My man Ailill will accompany you, if that’s acceptable.”

Abbot Columb shrugged. It did not matter to him. So the man at Airtre’s left side spurred his horse forward, and as he approached Columb, the old abbot turned his own mount, and side by side they rode toward the monastery’s gate, which was swinging open to greet them.

The Treasure of St. Aiden… Columb mused as he rode through the driving rain. Here was an ancient tale that had plagued him for years, and abbots of the monastery before him. No one, of course, believed that the treasure had been secured by St. Aiden himself, who had founded the monastery almost three hundred years earlier. That was simply the name given to this alleged hoard of gold and silver and such that was supposedly hidden somewhere within the walls, hidden so well it had been overlooked by the successive bands of Northmen who had sacked the place.

Neither Columb nor anyone else knew where this legend had come from. It was true that Ferns was a wealthy monastery, and the abbot and a few others, a very few, knew the truth of why that was. But there was certainly no Treasure of St. Aiden.

At least he has not gone up into the hills, Columb thought. If there was one advantage to the legend of the treasure, it was that men like Airtre or the heathens before him came looking for riches at the monastery and did not go blundering around the hills to the north. And that, to the abbot, made this sort of annoyance, the sort that Airtre was visiting on them, worth it.

The abbot glanced over at the man named Ailill who was riding beside him. They walked their mounts through the gates. Columb pulled his reins a bit and his horse veered off to the right and Ailill did likewise.

There was a cocky arrogance on the man’s face, so typical of these young warriors, Columb thought. They rounded the end of the gate where dozens of armed and mounted men in the abbot’s service had been hidden from view. Columb tried not to take any satisfaction as he saw Ailill’s expression turn from haughty to surprised to panicked.

Ailill began to make a strangled cry, but before he could get much sound clear of his throat, four men were on him, dragging him down from his saddle and into the mud. Three of the men pressed feet down on his shoulders and legs while the fourth used his foot to press the man’s face down in the soft earth to keep him from crying out.

Standing over the man, sword drawn, was Brother Bécc mac Carthach. Brother Bécc was wearing a padded tunic under a mail shirt, and there was nothing in his dress or gear that would suggest he was a monk—which he was—save for the large, crude wooden cross that hung from a leather thong around his neck.

Bécc looked up at Columb, his long dark hair plastered to his head. Only one eye, the left eye, was visible on his half-ruined face. The other eye, along with the flesh on the right side of his face, right down to the bone, had been eliminated by the downward slash of a Northman’s sword in a fight long before Bécc had sought refuge in the church.

Incredibly, the man had not died. Hard scar tissue had grown over the place where his eye and his skin had once been, and Bécc had given thanks to God and devoted his life to the service of his Lord, bringing his devotion and his particular abilities to that cause.

Now, as ever, he looked to Columb for direction. Columb shook his head. No more communication was needed, and Ailill did not even know that the abbot had just spared his life. Bécc gestured toward one of his men, who stepped over and quickly gagged and bound Airtre’s squirming man-at-arms.

Columb turned his eyes from Ailill, still sprawled in the mud, to another man, mounted, wearing mail and a helmet, sword also drawn, watching from a dozen feet away. The man looked up from the thrashing Ailill and met Abbot Columb’s eyes. The abbot nodded his head to this one as well, and as with Bécc, no more words were needed.

The mounted man, named Faílbe mac Dúnlaing, raised his sword and shouted, “Go! Go!” He kicked his heels into his horse’s flanks and the beast leapt forward and the men behind did likewise, twenty horses streaming past Abbot Columb and his tired mare, and behind them another forty men on foot, armed with spears and axes and many wearing leather armor and bearing shields. Faílbe was the rí tuath of the lands to the west of Ferns, a friend of the monastery, a wealthier man than Airtre, and soon wealthier still once Columb compensated him for his efforts in driving Airtre away.

As those men who had gathered for the defense of Ferns charged out of the gate, Brother Bécc mounted and led the monastery’s twenty-man house guard after them, so that they, too, might join in the fight. Columb might not have the Treasure of St. Aiden, but he was not without resources.

As the last of the soldiers raced past, Columb swiveled his horse around and took a few steps forward to where he could see out the still-open gates to the battlefield, if such it could be called, beyond.

The mounted warriors streaming out of the monastery gates seemed to have taken Airtre and his men entirely by surprise. The Irish did not as a rule fight mounted. They were more likely to use their horses to get to a fight and then dismount and do battle on foot. But Columb and Faílbe had agreed that the terrifying sight of a massive horse and sword-wielding rider pounding down on them might be just the thing to make Airtre’s men break and run.

And they were right. Columb could not see much, with the rain and the distance and the press of men, but he could see the soldiers who formed Airtre’s line frantically taking up their shields and positioning their weapons and bracing for the shock of the riders barreling into them.

Airtre himself and his men-at-arms were not so thrown off by the surprise. They began to move immediately, riding toward the threat, swords held high, spears leveled. But Faílbe’s men all but ignored them, going instead for the vulnerable, lightly armed, frightened men in the line.

It worked just as they had hoped. The horsemen were still fifty feet away when the first of Airtre’s unhappy, conscripted soldiers flung his weapons aside and ran, followed almost instantly by the next and the next. By the time the riders reached the place where the men had been making their stand, they were all in flight.

Despite that ignominious retreat, there were still some men ready to fight. Airtre and his warriors, too proud to run without first making a stand, spurred their horses forward to meet the attack. They charged into Faílbe’s riders, exchanging blows with swords, lunging with spears, swirling around and around in that odd dance of mounted combat. The ring of steel on steel, the shouts of fighting men came in sharp bursts through the muting rain.

Columb watched with interest. The only question really was how long Airtre and his men would keep it up before they, too, ran off, and if many would die before they did. Columb really did not care to see men die, not even men like Airtre, and he said a silent prayer that God might break Airtre’s will and send him running off.

It was not long at all before the prayer was answered. The fight was entirely one-sided, hopeless for Airtre and his men-at-arms once they had been abandoned by most of their men. First one of Airtre’s guard, then another and another broke off from the melee, spun his horse around and raced off down the muddy road, where the foot soldiers were already nearly lost to sight. Airtre was last to go, but go he did, and well before his escape could be cut off.

Brother Bécc was willing, indeed eager, to pursue Airtre to the end of the earth and tear the man’s liver out when he got there. But he had only twenty men under his command, and that was not enough, even against such poor soldiers as those Airtre commanded, and Faílbe’s men had no intention of pursuing the defeated men.

This, too, was planned. Much as Columb loathed Airtre and his greed and ambitions, he did not want to precipitate a slaughter of Airtre’s men. Faílbe, for his part, did not care to go chasing all over the countryside while leaving his own tuath unprotected. So it was agreed: Faílbe would drive the insolent raiders away from the monastery at Ferns, but would do no slaughter beyond that.

And Faílbe was a man of his word. His horsemen chased Airtre’s no more than a hundred yards down the road, making no real effort to catch them, then reined to a stop and watched them racing off over the dull green fields. When at last they were certain that the raiders were leaving and would not be back soon, they turned and walked their mounts back toward the monastery gates.

A few men lay on the battlefield, wounded, perhaps killed, and Abbot Columb moved his horse to one side to allow a cart to pass through the gates to collect them up. Faílbe and Brother Bécc rode past the wounded with hardly a glance. They came in through the gate, their men-at-arms, mounted and otherwise, trailing behind. They reined to a stop in front of the abbot.

“I congratulate you on the victory God has given you,” Columb said. Faílbe nodded, gave a weak smile as if he found that idea slightly amusing and nothing more. Brother Bécc crossed himself and bowed his head, then looked up again.

“There is food and ale and a fire in the hall for you and your men,” Columb said next, and that was greeted with greater enthusiasm.

True to Columb’s promise, the food and drink were plentiful, the fire in the hearth in the center of the floor built to a height that nearly threatened the thatch overhead, and it was not long before Faílbe and his men were full and nearly dry, their corporeal needs satisfied at least, and that was as much as Columb could hope to do. The abbot did not think they were the sort who worried too much about their spiritual needs.

“Let me raise a glass, Abbot,” Faílbe said.

He and the abbot were seated at the head table, the remains of their meal in front of them, the light of the fire dancing off their steaming clothing. Bécc, too, sat with food and drink in front of him, but there was nothing that Columb could read on the man’s face. That was usually the case. He wondered if that was because of the monk’s natural stoicism or the damage his face had endured. Both, the abbot concluded

Columb lifted his cup. Faílbe had already raised quite a few glassfuls to his lips, but Columb would begrudge him nothing after the aid he had given that day.

“To the Treasure of St. Aiden,” Faílbe said. His face was adorned with his half-amused smile so Columb raised his glass higher still.

“To the Treasure of St. Aiden,” Columb said. “May it continue to not exist. As a story for children it is trouble enough. I can’t think what agonies it would bring if it were real.”

The two men smiled. And drank. And Brother Bécc drank and said nothing.

The damned Treasure of St. Aiden… Abbot Columb thought.

“Well, I thank you, Faílbe mac Dúnlaing,” Columb said next, “for coming to the aid of the monastery. The Lord looks kindly on such things.”

“Let us hope,” Faílbe said. “I can use all the help I can get. But of course I am happy to come to your aid, Abbot, when I am able. Which I am now, but might not be soon.”

“Things are stirring to the north?” Abbot Columb asked.

“Things are stirring in the household of the rí ruirech, Tuathal mac Máele-Brigte,” Faílbe said. “There are those in his family who would cut his throat to gain the rule of Laigin, and I think they soon will. Right now they're all too busy intriguing against each other to worry about us here. But if Tuathal is killed, his successor might turn his attention this way. And if that happens I will be lucky to save myself, let alone a monastery.”

“We will pray that does not happen,” the abbot said.

A sudden draft made the candle flames dance, the sound of the rain came louder, and the two men looked up to see the door to the hall flung open. A very wet, very weary messenger stood in the frame, looking for the one to whom he should speak. His eyes settled on the abbot and his guest, men of obvious authority, and he pulled the door closed and hurried over.

“This does not bode well,” Faílbe said as the two watched the rider approach.

“Abbot Columb?” the man asked, stopping at the head table and giving a shallow bow.

“Yes,” Columb said. “And this is Faílbe mac Dúnlaing, to whom you should also give honor.”

The rider looked at Faílbe, gave another shallow and impatient bow, then turned back to Columb. “I come from Abbot Donngal, from the monastery at Beggerin,” the man said.

Columb nodded. The monastery was about fifteen miles south, overland, right at the mouth of the River Slaney. “Yes?” he said.

“The abbot begs to say that the Northmen have landed there!” the messenger gasped. He had clearly been wanting to get these words out for some time.

“The heathens! There are hundreds of them, many hundreds, and a fleet of ships, and he is sure they are set on slaughter!”

Columb nodded again, unable to work up as much enthusiasm as the wet rider. “I see,” the abbot said. “And is there anything Donngal would have me do about this?”

The messenger straightened a bit, frowned a bit. “Well, if there are any who could come to the aid of Beggerin, the abbot says that would be most pleasing to God.”

God, indeed, Abbot Columb thought. “Well, there is naught that Ferns can do. We have only a small house guard, not much more than does Beggerin.” He turned to Faílbe. “What say you? Can you bring your men to aid Beggerin?”

“I cannot,” Faílbe said. “Once the heathens have had their way with Beggerin they will come up the rivers, and that means they will soon come to my lands. It’s my duty to see to the safety of my own people first.”

Columb turned back to the young man standing wide-eyed before him. “Please tell your abbot what you heard here, and thank him for his warning. I am sure God will protect Beggerin from the ravages of the heathen. But first I beg you to dry yourself and have some food and drink. On a night such as this, I don’t think that the heathens will be at our doors anytime soon.